Communicating the Beauty in the Abstract

Credit: Tico Mendoza

AUDRICK PYRONNEAU, Ph.D. Student, Mathematics

Audrick Pyronneau, math Ph.D. candidate and NSF Graduate Research Fellow, studies the properties of geometric shapes.

Interviewed by Marc Airhart

How did you end up choosing mathematics as an undergraduate?

I switched to math from being a pre-med major. I really started liking it in an abstract algebra class. This is a class where you take everything you know intuitively about math and then you build up formally from there. For example: when is A+B actually equal to B+A? This is a property called commutativity, and we examined why it is or isn’t true. This was the first time I really saw something that was completely abstract but could still be described – an idea instead of a real thing. I thought that was really fascinating.

And did that hook you?

Yeah. Artists and poets can capture ideas really well that are not expressible in words, but I always felt like I had trouble communicating ideas. I really saw math as a way to describe ideas and put them down rigorously, to take a really hard concept I need to understand, an idea in my head, and express it in a way that someone else can understand it, too. This is why mathematicians will say, “Oh, this proof is beautiful.”

Do you have much experience communicating about mathematics to non-mathematicians?

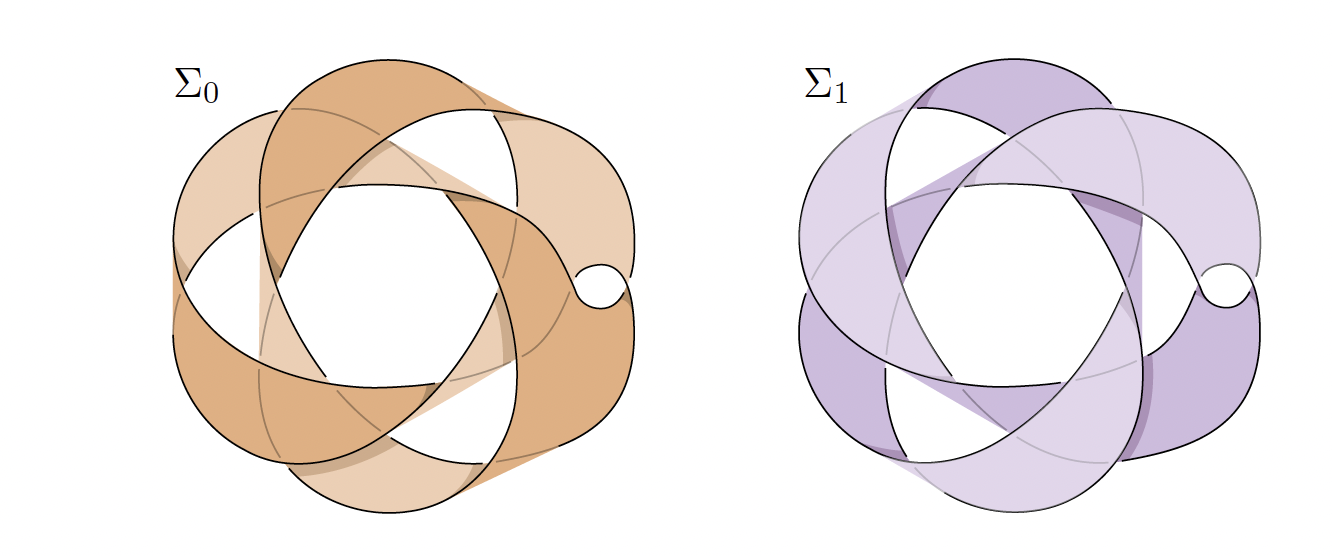

UT has a program called Sunday Morning Math Group. A lot of high schoolers and middle schoolers come to campus and a grad student will give a talk. I talked about topology, which is what I do. I had this exercise called “Knotted Up,” where I gave the kids and their parents string and a knot configuration that they had to get out of. And then I gave a mathematical proof of why you could actually pull off this unknotting. Or, you know, my party trick: I tell people I study how two dimensional shapes look in four dimensions.

“My party trick: I tell people I study how two-dimensional shapes look in four dimensions.”

So, I’m imagining a string, made into a knot in three dimensions, and your work then puts that into a fourth dimension somehow. Why is that important?

That’s kind of the beauty of mathematics that I was alluding to earlier: this concept that has no physical properties I can touch, but I can still describe it to other people. Physicists care about knots because they can be useful for describing things in the real world, like vortices in moving fluids. But usually the trickle-down effect from mathematics to real-world applications takes a long time. One of the best parts of this work to me is I always have something that I’m learning and trying to describe, and I work with students and get to give them a new idea.

Why did you choose UT for graduate school?

I chose UT because the year I got in, they hired four great topologists in my subfield—Lisa Piccirillo, Maggie Miller, Irving Dai and my advisor Anthony Conway. Lisa wrote a very famous paper in the Annals of Mathematics while she was still a graduate student at UT. And both she and Maggie—also a UT alum—won the Maryam Mirzakhani New Frontiers Prize, which is one of the Breakthrough Prizes for early career women in mathematics. It was already historically a very big school in topology, and then they bring in four new topologists, which is kind of unheard of in academia. So it seemed like an exciting time to be here.

You’ve mentioned enjoying the environment and community at UT. What stands out?

One of the best UT experiences is going to a football game at night, seeing a drone show and the fireworks. And I get to meet people in the other graduate programs: you start out talking about math, physics and astronomy, then you’re going to a football game with them or Latin dance. Some aerospace students had an eight-ball team named Pocket Science. I joined as their representative of math to play pool – you know, geometry – and the aerospace students tell me about inelastic and elastic collisions, how the cushions are going to give a little bit so it’s going to kill the angle. We’ve talked about this hard core.