One Scientist’s Random Walk

Credit: Tico Mendoza

STELLA OFFNER, Ph.D.

Stella Offner, professor of astronomy and director of the National Science Foundation-Simons AI Institute for Cosmic Origins.

Interviewed By Marc Airhart.

How did you end up being an astrophysicist?

In college, I was interested in physics, math and computer coding. I think success and happiness in a career involves finding the challenges that engage us. Some people like to struggle with writing, and some people like to struggle with creative things. I really like struggling with numbers and programming, and I would lose large chunks of time, engrossed in my homework. I also enjoyed the analytical problem solving of physics.

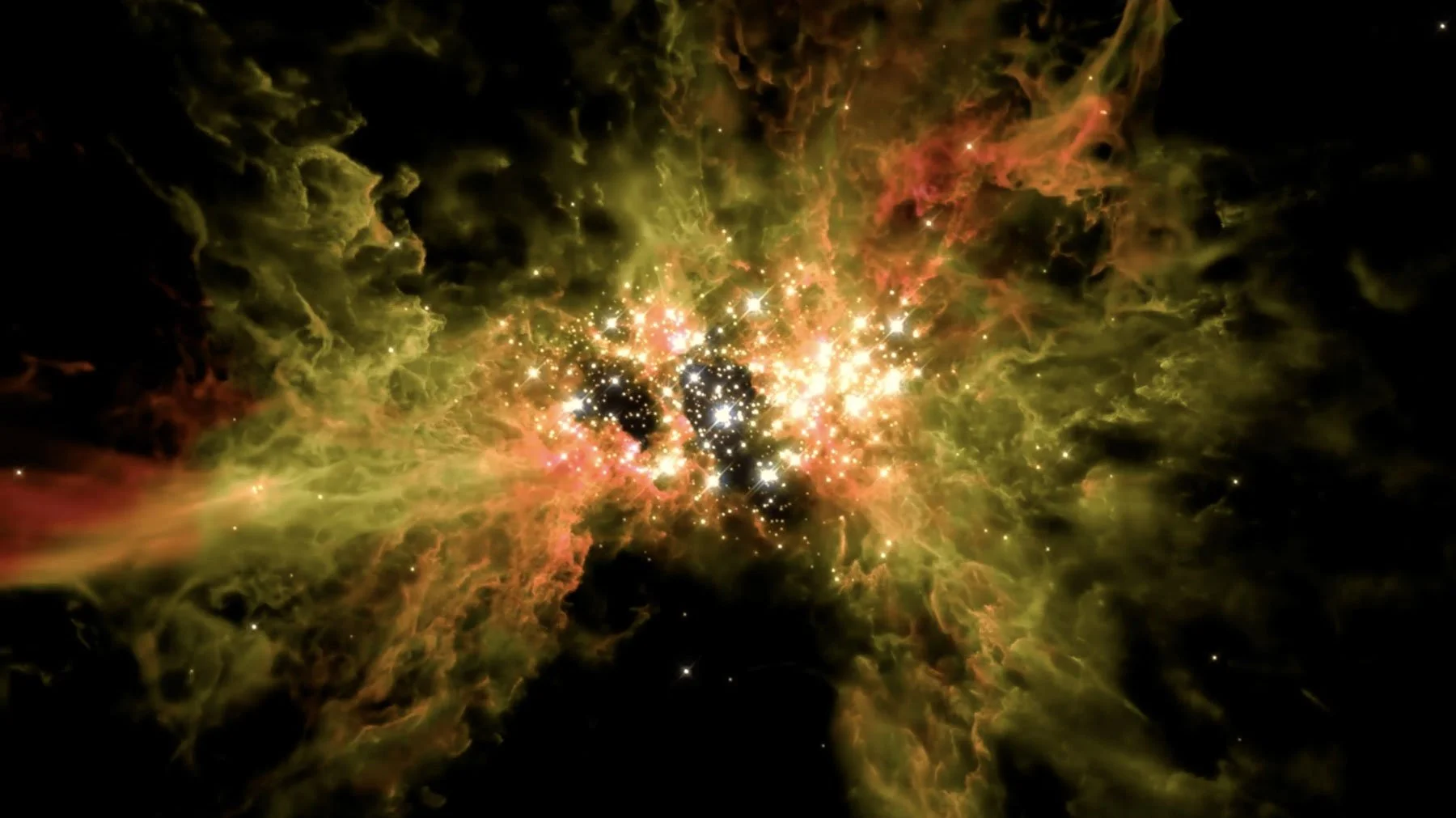

In graduate school, I became fascinated with the idea of using high performance computing to model physical systems. Astrophysics is a beautiful science, and there’s a real connection between computer simulations and what we observe in the universe. The simulations are a laboratory that allow us to explore times and scales that we can’t directly observe. That made computational astrophysics very engaging for me, in a way that was different from other computational sciences.

“I think success and happiness in a career involves finding the challenges that engage us.”

How did you first get interested in researching how stars form?

Star formation has some of the most interesting physics. There’s hydrodynamics, magnetic fields, radiation, and gravity. There’s also really cool fluid dynamics like turbulence. So I was fascinated by the very complex interplay of different types of physics across different scales. My graduate school advisor was Christopher McKee, one of the giants of star formation, who is now retired. He was a pen and paper theorist who worked with a collaborator, Richard Klein, on modeling these systems with computers. What you work on in grad school is just a leaping off point.

You started out in grad school modeling star formation, but you’ve branched out a lot since then, right?

Over the past 10 years, when I saw opportunities, I moved into those areas. That’s how I ended up working on astrochemistry, cosmic ray physics and machine learning, none of which were part of my Ph.D. research. I’ve also worked on galaxy formation and planet formation. As we say in physics, life is a random walk where each step, you go one way or another and eventually you wind up somewhere completely different and unexpected than where you started. I’m just a curious person who’s somewhat restless and always looking for new things.

How did AI become part of your work?

In astronomy, it’s very hard to create large, labeled datasets from telescope observations, since we simply don’t know the ground truth. Historically, we’ve relied on experts – and more recently citizen scientists – to hand-label the data. But that’s very slow, and there’s a lot of uncertainty. However, we can create very accurate, large-scale computer simulations and know on a pixel-by-pixel level exactly what is happening. About 10 years ago, I realized that my simulations could generate very large datasets to train AI models to classify data, identify features and test new models. That idea made me very interested in pursuing machine learning and AI.

And now you’re the director of the National Science Foundation-Simons AI Institute for Cosmic Origins (a.k.a. CosmicAI), an institute that’s developing new AI methods to solve astronomical challenges. What kinds of things are you doing there?

One exciting CosmicAI project aims to use AI to make astronomy research more efficient. We developed a benchmark, AstroVisBench, to test large language models (LLMs) like Claude, Gemini and ChatGPT to see how well they can read, analyze and plot astronomy data. On the first try, the current models still make a lot of errors or create code that crashes. This means that scientists have to work iteratively with the models, finding where things go wrong and having a back-and-forth dialogue, but often getting useful results in the end. In science in particular it is critical not to use these models blindly. You have to understand the fundamental context of your question and the reasoning and data behind any model prediction. The LLMs are just helping to speed up the research process but can’t replace the researcher and expert knowledge.